Righteousness > Justice

- BOO

- Jul 26, 2025

- 25 min read

Love and faithfulness meet together; righteousness and peace kiss each other. ~ Sons of Korah (Psalm 85:10)

Since a couple recent studies in our Sermon on the Mount series have centered on righteousness and justice/judgement, I thought I would put some of my thoughts here that didn't make the final cut in those posts. Welcome to the deleted scenes. (For the original articles, see here and here.)

This post really gets into the weeds on Geeky Greeky stuff and may not add much to our walkthrough of the Sermon on the Mount. It really is just me working things out primarily for myself. I leave it here in case you feel like Bible nerding out with me. Otherwise, move along - there's nothing to see here.

---------------

Why Words Matter

Humans have a drive for justice. A young child's proclamation "But that's not fair!" is an early manifestation of this instinctive value.

So, what is the role of the Church regarding justice? Should we be fanning into flame this drive for fairness, or releasing justice into the hands of God? What are the implications of Jesus' New Covenant emphasis on limitless forgiveness and grace for all - decidedly unfair concepts.

Sometimes the very words we use to approach this topic can cloud our understanding and make it more difficult to see what Jesus is actually teaching. For instance, while "justice" is a currently popular concept within our culture and within many Christian circles, the Bible gives us a better word for the Church to rally around - righteousness. And I'd like to investigate the difference together.

Most of us take words for granted and never pause to think about their world shaping power. Genesis tells us that God created our world through words, speaking everything into existence (Genesis 1). And John's Gospel tells us that those acts of creative speech were actually God creating the world through the Word, who was with and who was God (John 1:1-3, 14). Our universe exists and is held together by, and is ultimately redeemed, rescued, and restored by the Word of God who is Jesus (Colossians 1:15-20). So this truth should come as no surprise:

Our world runs on words.

I recall learning in university how our vocabulary actually impedes or enhances our thought process. Linguistic Relativity Theory (or the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) suggests that the language we know can shape how we experience the world around us. The words we know and use become the building blocks for our thoughts, or at least ways for us to crystalize our intuitions or sensations into communicable ideas. When the language we use doesn't give us words to express a particular thought, for instance, that idea can be more difficult for us to wrap our minds around and/or share with others. Wordless thoughts tend to remain at the level of a hunch or an intuition without finding full clarity in our minds. This is why sometimes we might hear a person articulate something with clarity and it feels like they have given us words to express something we may have been sensing but couldn't fully frame in our minds.

As numerous studies have demonstrated, expanding our vocabulary and being clear about definitions can expand our consciousness. Limiting our language, restricting or reshaping definitions, and policing word usage are ways societies can shape cultural consensus, and even practice a form of mind control, like the "newspeak" of George Orwell's novel 1984.

Whether for good or for bad, all cultural change must include ideological change, and all ideological change must include linguistic reshaping.

This reality is not evil, it is just the way the human mind works in our world made by words. Christian discipleship, for instance, includes learning new words and new meanings which can unlock new thoughts and new ways of being in this world. But like all good things, the world-shaping power of words can be a tool that is used for unhealthy ends if we do not steward our words carefully, biblically, Jesusly. (There I go, making up a word to express a thought.)

All of this has profound implications for everything from our theology to our therapy, our ethics to our empathy for others who see issues differently. So it is always worthwhile to pay attention to how the words we use are influencing the thoughts we have. And yet, we must do this with wisdom and grace, so we avoid becoming word police or language legalists.

"To have a second language is to have a second soul." ~ Charlemagne (748 – 814)

So now, on to talking about two particular English words, their linguistic roots, and their practical implications for followers of Jesus: Righteousness and Justice.

We should all be aware that we approach this topic within a specific point of time and space. Currently our Western world highly values the actual word "justice", so much so that, with the help of qualifiers, we press the word into service to mean almost everything that we believe is right. People now talk about everything from economic justice to environmental justice to racial justice to reproductive justice. It seems that if any individual or group wants to claim the moral high ground for their cause, a first step is to hyphenate it as [insert cause here]-justice.

Some researchers list a dozen or more types of justice talked about today. The most basic categories include:

Retributive justice (Focuses on proportional punishment.)

Restorative justice (Focuses on relational repair and healing for all)

Communitive justice (Focuses on living in right relationship with others)

Distributive justice (Focuses on the fair sharing of benefits and burdens in society)

Social justice (Focuses on correcting societal systems that lead to inequality)

My thesis for this article is that the Church is called to manifest a different ethos and ethic than our surrounding culture and that Jesus gives us a better word, and a better concept, than justice to strive toward: and that is righteousness.

What is Justice?

If we think of justice as "making wrong things right" then we could argue that justice is part of the role and goal of the Church. But our idea of "justice" typically includes the methodology of laws, law enforcement, retribution, and punishment in order to make things fair and equitable.

When the word "justice" is used without qualification, it usually means retributive justice - making laws and enforcing punishments for breaking those laws in order to encourage good behaviour and discourage bad behaviour. Some Christians add a qualifier to speak about restorative justice, which is closer to the biblical word "righteousness".

In any society, justice is a good value. But is it the best way to think about the role of the church in society?

The Evolution of "Justice" in the Church

When I was a kid in the Evangelical church community, I remember hearing that "justice" was a bad thing, because if we all got exactly what we deserved and everything was fair, we would all end up in hell. The point was that thankfully, God goes beyond justice to mercy, and this is our hope. God's righteousness is given to us as a gift of grace, not as a fair wage we earn through our good works. The Gospel, we believed, was the opposite of justice.

For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord. ~ The apostle Paul (Romans 6:23)

For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith — and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God — not by works, so that no one can boast. ~ The apostle Paul (Ephesians 2:8-9)

Mercy triumphs over judgment! ~ The apostle James (James 2:13)

We were taught that God does not deal with us according to justice, but according to grace, received by faith. And we are called to relate to each other in the same way - according to the values of grace, mercy, and peacemaking. Freely we have received; freely we must give.

I think our older Evangelical understanding of the Gospel was incomplete, but it wasn't wrong. The Gospel says more than salvation by grace through faith, but it does not say less. We cannot let this beautiful truth slip into the background of our theology and ethics.

When I was a young pastor at a Baptist church in the early 1990s, I remember playing a song in our Sunday service that emphasized this point. The style isn't my typical musical preference, but the message seemed important enough to share with the congregation. The song - Beyond Justice to Mercy - illuminates the truth that all our intimate and important relationships - with friends, family, and church family - would fail if we put justice first. It made good sense to me then, and it feels like an even more urgent message for the Church today:

Then as we moved into the 2000s, I noticed a shift within the Evangelical community. Christians began to talk more than ever about pursuing justice as a high value. Instead of justice being a negative thing in the Gospel economy (justice = damnation; grace = salvation), justice became a good thing in our Gospel expression. Christians were now supposed to pursue justice.

I think this change came from a good place. We Evangelicals were realizing that our understanding of the Gospel was too skewed toward two imbalances:

We emphasized God's interest in the individual at the cost of the communal.

We emphasized God's interest in saving souls for heaven at the cost of understanding what the Kingdom of heaven coming to earth meant for our lives here and now.

I knew enough of the Bible to affirm this course correction within the Church's understanding and expression of the Gospel. But I didn't know enough to recognize the Trojan Horse of "justice" being welcomed in under the banner of Kingdom theology. (By "kingdom theology" I'm talking about the appropriate expansion of our understanding of the Gospel beyond "God wants to take us to heaven when we die" to include "God wants to bring his kingdom of heaven to earth here and now".)

And so, I got swept up in this linguistic drift. I started to assume everything people passionately proclaimed and paraded about justice was all true, all biblical, all Jesusy. After all, there are a few popular Bible verses that champion justice right alongside righteousness, aren't there?

Learn to do right; seek justice. ~ The prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 1:17)

But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream! ~ The prophet Amos (Amos 5:24)

He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To do justice and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God. ~ The prophet Micah (Micah 6:8)

So there it is. The Bible tells us to prioritize justice. Even Jesus affirms this. When rebuking the religious leaders of his day, Jesus says:

You have neglected the more important matters of the law—justice, mercy, and faithfulness. ~ JESUS (Matthew 23:23)

And so I joined "Team Justice" and was ready to lend my voice to the chorus of Christians crying out for fairness in this unfair world.

But that all started to unravel years ago.

Jesus & Justice

I remember how my journey to seeing things differently began.

At first I noticed that some of the more justice-oriented people in our church were importing ideas that seemed patently unchristian. These ideas were dividing us more than uniting us, and I was beginning to wonder why such a good value as "justice" was not bearing the good fruit it promised. At first I assumed I was missing something. Perhaps my age, my gender, my ethnicity, my personal history and other immutable characteristics were blocking my mind from understanding the truth. I wanted to remain humble and helpful and open to learning. But the questions kept growing.

Then I remember being asked to speak at a conference on the theme of "Jesus & Justice". So I set to work doing my research and message prep. I knew they anticipated me sharing motivational and inspirational reasons why Christians should be social justice advocates and activists and why this is the will of Christ for his Church.

But over the weeks leading up to the conference, my research was not being as productive as I was hoping. I had to deal with two speed bumps in particular:

Most of the positive justice talk in the Bible is in the Old Testament. The concepts of justice (mishpat) and righteousness (tsedek) are equally encouraged and often appear alongside one another (e.g., Psalm 97:2; 103:6; Proverbs 8:20; Amos 5:21). So, in the Old Testament, justice is a big deal for God's people to practice. This makes the change in the New Covenant all the more sharp and meaningful. Remember that being in the Old Testament doesn't discount a biblical truth, but it does mean we have to at least ask how the teaching translates into a New Covenant context. Jesus. Changes. Everything. Sometimes an Old Testament teaching serves to highlight the difference the New Covenant makes. After all, in the Old Covenant, God's people were forming an earthly kingdom with a political government and actual laws with real punishments for breaking those laws. The Old Covenant kingdom was political, geographical, ethnic, and often violent. This is different to the values of the New Covenant community of faith. The Old Covenant gave us "an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth" under the banner of justice. But Jesus specifically undoes this way of thinking in the Sermon on the Mount. So just because something is "in the Bible" doesn't mean we follow it without asking how Jesus would help us interpret and apply it. I have found that most Christians know this principle of Scripture interpretation (don't follow the Old Testament without first asking how Jesus and the New Covenant change our understanding and application), but on the topic of "justice" they ignore it.

Jesus may have challenged the Pharisees' hypocrisy for not living up to their own standards of justice, mercy, and faithfulness, but that falls short of actually teaching these ideals for his own disciples. In fact, I couldn't find one passage where Jesus teaches his own followers to pursue justice. Not one. Like, never. You would think with all the social justice talk within Christian circles these days, it would be a major theme of the New Testament. But it isn't. In fact, not only does Jesus never command it, neither do his apostles. Justice, I had to admit, is not a New Testament ideal for Jesus People.

All of this new information was getting in the way of what was supposed to be a rousing plenary session at the "Jesus & Justice" conference.

What I did notice is that Jesus repeatedly calls his disciples to pursue, not justice, but righteousness. Just in the Sermon on the Mount we see three instances:

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. ~ JESUS (Matthew 5:6)

For I tell you that unless your righteousness goes above and beyond that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of the heavens. ~ JESUS (Matthew 5:20)

But make it your priority to seek the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. ~ JESUS (Matthew 6:33)

And again to be clear: there is no similar teaching from Jesus regarding justice. It just isn't there. I was beginning to realize why, whenever Christian leaders preach about justice, they quote the Old Testament and never Jesus. We don't quote Jesus on justice because we can't quote Jesus on justice. And the same goes for the rest of the New Testament.

I wondered - maybe righteousness and justice are synonyms: two different English words for the same biblical concept. So, wherever Jesus says "righteousness" maybe we can just swap in "justice"? But I quickly learned that this idea was more wishful thinking than honest textual engagement.

It's Geeky Greeky Time

I found out that these two concepts - righteousness and justice - are similar, with lots of overlap, but the differences are crucial. When we get this wrong, we become entangled in a thousand theological confusions that have real world ethical implications.

In order to make it make sense, we need to do some geeky Greeky study. Sorry this is about to get real nerdy all up in here....

In our English Bibles, two Greek words are sometimes translated as "justice" - ekdikésis and krisis.

Ekdikésis means to make things right forcibly through punishment, retribution, or vengeance, and this is something that disciples of Jesus should leave in God’s hands. Ekdikésis is retributive justice and is expressed in the motto: "an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth".

This is the word used in the Parable of the Unjust Judge in Luke 18, where a woman seeks "justice" or avenging for the wrong done to her. This is the only passage where Jesus even appears to teach on the topic of justice (he's really teaching on the topic of prayer), and his conclusion is straightforward: we can pray for God to act in bringing justice/vengeance, but we should not pursue it ourselves. That would mean "taking the law into our own hands" and it attempts to usurp the role of God.

This fits with what wise King Solomon says:

Do not say, “I’ll pay you back for this wrong!” Wait for the Lord, and he will avenge you. ~ King Solomon (Proverbs 20:22)

And in case there is any doubt, the apostle Paul confirms what Jesus teaches with clear and unmistakable wording:

Never take revenge (ekdikeō, the verb) yourselves, beloveds, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: “Vengeance (ekdikēsis, the noun) is mine; I will repay,” says the Lord. ~ The apostle Paul (Romans 12:19; quoting Deuteronomy 32:35)

The apostle Paul goes on to talk about how God will often work out his justice/vengeance through governments, not the church (also see 1 Peter 2:14). We can pray for this kind of "justice", and we can trust God to bring it, but we cannot try to make it happen ourselves. It seems this kind of retributive justice is too strong of a punishing power for the Church to be trusted with. Our attempts at vengeance are almost always tainted by ego, anger, and a desire to harm rather than heal. As Christ-followers, we have a different path to walk.

Jesus never calls his followers to fight for justice, but to pursue righteousness.

EXCURSUS: The curious case of 2 Corinthians 7:11. Please feel free to skip this excursus. It's way too much detail for a blog, even this one, but I had to work it out in my head and this is how I do it. Okay you've been warned. Read further at your own peril... In his second letter to the Corinthian church, the apostle Paul says something that seems contradictory: he says that he has seen their ekdikésis (judgement/vengeance/punishment) and commends rather than condemns it. He sees it as a sign of the congregation's repentance for their former unrighteous celebration of sin (see 1 Corinthians 5). Yet, as we have seen in Romans 12:19, Paul quotes God in Deuteronomy 32:35 to condemn our involvement in ekdikésis. How can Paul commend in one place the very thing he condemns in another? Here are four thoughts: 1) Language Elasticity. Ekdikésis, like most words, has semantic range; it can mean different things in different contexts. As NT Wright often says, language always functions within a story. Ekdikésis can sometimes mean something closer to discipline or accountability rather than pure vengeance (and it shows this range in the LXX as well). This is why, in 2 Corinthians 7:11, most English Bibles translate ekdikésis as something softer like "justice" or "vindication" or "zeal to see the wrongdoing punished" rather than "vengeance" as they do in Romans 12:19. Language elasticity is definitely a fact, and in this instance it is a doorway to understanding, but likely not the full answer. 2) Descriptive VS Prescriptive. In 2 Corinthians 7:11, Paul is being descriptive not prescriptive. He is not telling Christians they should be punishing, but he is observing that the Corinthian Christians have shown how much they are learning to take sin seriously by moving from celebrating sin to opposing it. Still, he never then encourages them to keep this attitude up. To the contrary, in 2 Corinthians 2:5-11, Paul tells them to move from church discipline to church compassion. Their ekdikésis showed they had matured enough to stop abusing grace as a license to sin - great - but now they needed to mature even more and follow the way of grace, mercy, and peace. So, Paul is commending a trajectory, not a final goal. The trajectory Paul is commending in the Corinthian church is: Moving from CELEBRATING SIN to TAKING SIN SERIOUSLY to ultimately TAKING GRACE SERIOUSLY. 3) Outsiders VS Insiders. The difference is the focus. In Romans 12:19, ekdikésis is directed outward toward our "enemies", and that is clearly wrong. In 2 Corinthians 7:11, ekdikésis is directed inward, as a sign of the church taking their own sin seriously. Paul may be referring to the final stage of the "Church Discipline" (I prefer "Church Restoration") process laid out by Jesus in Matthew 18:15-17, then addressed by Paul in 1 Corinthians 5 and 2 Corinthians 2:5-11. It is a temporary time of separation, a consequence, a "punishment" of sorts. Except this form of ekdikēsis is not about "getting even". It is about getting well. It is the immune system of the body of Christ kicking in to fight an infection (never the person, but the attitude of autonomy that celebrates sin). This is a form of restorative justice in action, always hoping that this temporary exclusion of a person from regular fellowship will lead to their restoration (1 Corinthians 5:5). But, according to Romans 12:19 and 1 Corinthians 5, this kind of judgement or justice should never be directed toward non-believers. That would, according to Jesus, be casting pearls to pigs (Matthew 7:1-6). 4) Individual VS Corporate. Romans 12:19 is prohibiting individual retribution for wrongs suffered, whereas 2 Corinthians 7:11 allows some form of disfellowshipping as long as it is agreed upon by the whole church (probably a house church) - which is in keeping with the teaching of Jesus in Matthew 18. Individually, we don't try to take punishment for sin into our own hands. But corporately, as part of a process of eventual restoration, we may together as a church body decide that someone's continual unrepentance requires a stronger response. If this is the case, Jesus makes it clear in Matthew 18:15-17 that this kind of discipline (removing the unrepentant sinner from the congregation) is the last resort and final phase of a longer, relational, face-to-face process with the aim of helping the sinner repent and be restored. And Paul makes it clear in 2 Corinthians 2:5-11 that, even after temporarily disfellowshipping an unrepentant sister or brother, we still keep in touch, watch over their wellbeing, and are ready to care compassionately for them if/when their sorrow becomes overwhelming. A combination of all of these reasons may be why the apostle Paul commends rather than condemns the Corinthian Church's judgement/justice in this case. This one positive use of ekdikésis for Christians in the New Testament is not a contradiction when read with nuance. It is used within the context of a young church in process, as one stop along the way to full maturity in Christ. |

If we want to keep using the word "justice" positively in Christian circles, we should always remember to qualify it as restorative justice to distinguish it from retributive justice. Restorative justice is more about restoring shalom, personal growth, and mending relationships, always rooted in real repentance.

But what I have learned is that the Bible gives us a better word for this "restorative justice" idea that doesn't always require a qualifier - and that is "righteousness". We'll get to that after looking at one more Greek word that often gets translated as "justice"...

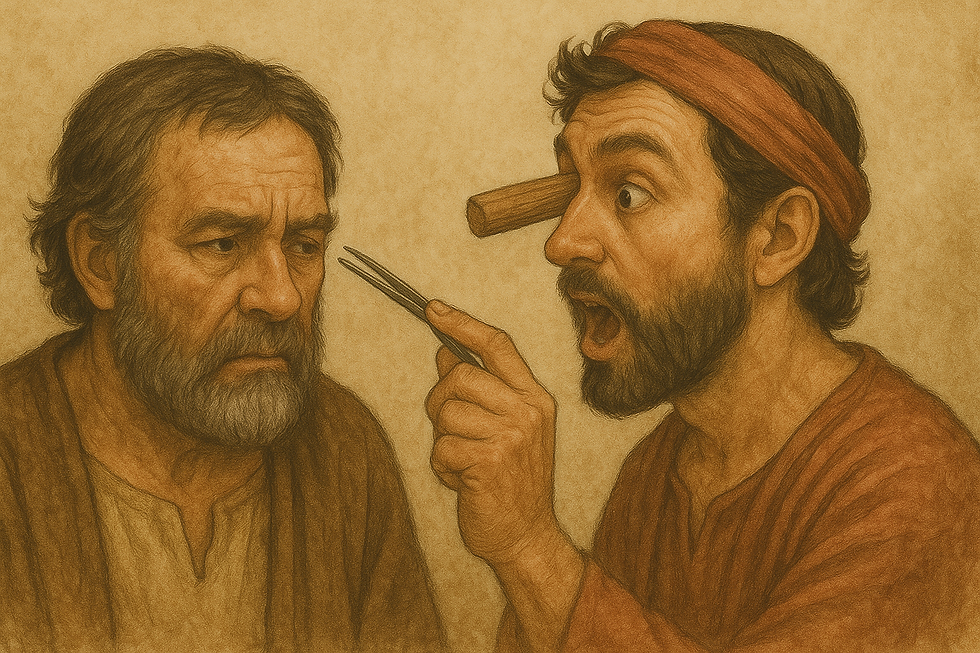

Krisis means to make a right judgement, and Jesus usually uses this word to refer to judicial or divine judgement (Matthew 5:21-22; 12:20; 23:23, 33; John 5:22-30; 7:24). Again this is a kind of "justice" that is not characteristic of Jesus followers. We don't sit in the seat of judgement, but leave that to God. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus straightforwardly says his disciples should not practice this form of judgement/justice - "Do not judge" (Greek, krisis), in Matthew 7:1. That seem pretty clear. Now, just to keep us on our toes, krisis is also used for making a judgement call, a decision, an assessment - something that we all do all the time. That's the thing with language, sometimes one word can be multipurpose, depending on the context. For instance, right after Jesus tells his disciples NOT to judge (krisis) in Matthew 7:1, he tells them to identify and help their spiritual siblings with their problems (which requires making a judgement call about something in someone's life being a problem in the first place). As an act of condemnation, krisis is a sin. But as an act of discernment leading to loving action, krisis is righteous (e.g., Matthew 23:23; John 7:24; 1 Corinthians 5-6). So we are not to judge as in condemning, but we are always to judge as in discerning. We may judge actions and attitudes as moral or immoral, but we never judge hearts. Bottom line, whether we use this word to mean judgement (wrong for us) or discernment (right for us), krisis is better translated "judgement" or "decision" or "discernment" rather than everything we import under the heading of "justice".

Both understandings of justice above - ekdikésis (vengeance) and krisis (judgement) do not communicate the restorative justice that the Church should practice. In fact, once you have to add the qualifier "restorative" to something to make it Christian, it might be time to find a better word. And thankfully, the Bible takes care of this for us.

Hopefully you're getting a glimpse of why "justice" is just too weak a word to capture the moral vision of Jesus for his Church. The scribes and Pharisees were the social justice movement of their time. But Jesus says his disciples must go beyond joining a social justice movement to forming a social mercy movement. This is real righteousness.

What is Righteousness?

Still being geeky and Greeky, the Greek word for "righteousness" is dikaiosuné (dee-kah-yos-oo'-nay, or, once more with flair, dee-kai-oh-SOO-nay). This word means to align our lives with God's will and God's way; to be in the right, especially in our relationships.

In short, righteousness is right-relatedness.

Jesus teaches us what righteousness looks like in the Sermon on the Mount and elsewhere, and it doesn't look like justice, at least not in the punitive or retributive sense of the word. In fact, righteousness isn't even about fairness. An eye for an eye is about fairness. But Jesus rebukes that idea in favour of the decidedly unfair ideals of mercy, forgiveness, and enemy love.

Righteousness is always restorative. Righteousness uses the relational tools of grace, mercy, peacemaking, forgiveness, and reconciliation to mend what is broken. Justice may be a good thing, but the life-changing, relationship-rescuing, sinner-restoring power of righteousness is something more, something better.

We can summarize the differences this way:

RIGHTEOUSNESS | JUSTICE |

Grace | Fairness |

Mercy | Judgement |

Peace / Peacemaking | Vengeance |

Forgiveness | Punishment |

Reconciliation | Correction |

Focus on responsibilities | Focus on rights |

Our Calling | God's Business |

Now here's the thing: Justice isn't bad for us; it just isn't good enough for us. Justice is good for earthly kingdoms. They would crumble without it. In the words of the famed American lawyer, Daniel Webster, on the topic of justice: "It is the ligament which holds civilized beings and civilized nations together."

This is true. And yet, God wants something even better for his kingdom of heaven on earth than being "civilized". He wants us to be communities that experience and express the healing power of shalom.

Righteousness > Justice

Some of us will have a voice in our head pop up and say: "But if you remove justice as a value for us to strive for, what will motivate us to live good lives? What will move us to work for change?"

Righteousness is better than justice for all these things. It's hard to help someone when you're judging them. It's hard to restore a relationship when you're condemning rather than forgiving. And ultimately, anything we think we need justice to motivate us to accomplish, love will do a better job.

And yet, as mentioned, righteousness and justice overlap in some ways. For instance, they both want some common goals, even if the ways they go about achieving those goals are sharply contrasted. Both righteousness and justice want a better world - they just have different ways of pursuing that goal. Both righteousness and justice care about moral goodness and ethical uprightness. But justice forces external behaviour while righteousness builds relational bridges to persuade hearts.

The Greek words for both actually point to this overlap. Notice that dikaiosuné (righteousness) and ekdikésis (justice/vengeance) both have "dik" in them. Both words are siblings from the same Greek family - the "Dik" Family. (While krisis - judgement/discernment - is more of a distant cousin from the Krisis Clan.) The Dik Family have this in common: every Dik cares about what is right. They just have different ways of getting there. (And if you had to read this last paragraph out loud in a group, my condolences.)

So, righteousness includes what we might call "restorative justice" but "justice" is not always restorative, and therefore, not always righteous for the Church to pursue.

If you know the story of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables, you know the difference between righteousness and justice, illustrated in the contrast between the characters of Jean Valjean and Inspector Javert. (If you don't know the story, and especially if you haven't seen the musical, it's never too late to repent of your sin and watch or listen to any version asap.)

So What?

Justice, rooted in prosecution and punishment, is a blunt instrument. It lacks the nuance, the tenderness, and the grace that human beings need to thrive. And I am concerned that our contemporary church seems to be drifting into an uncritical and undiscerning starry-eyed love affair with justice.

Two things are currently happening in our society at the same time that make for a deadly and divisive combination:

Our culture gives us new ways to screw up and have all of our moral failures recorded forever and easily shared (internet anyone?).

Our society is becoming increasingly judgmental, even merciless, for those moral failures all in the name of justice.

Writing for the Wall Street Journal, the Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist Peggy Noonan observes:

"The air is full of accusation and humiliation. We have seen this spirit most famously on the campuses, where students protest harshly, sometimes violently, views they wish to suppress. Social media is full of swarming political and ideological mobs. In an interesting departure from democratic tradition, they don’t try to win the other side over. They only condemn and attempt to silence." ~ Peggy Noonan (The Wall Street Journal: March 7, 2019)

As our callout culture and cancel culture grow more prominent while the sins we have record of grow more permanent and more accessible, we are doomed to become a more divided, condemning, and fractured society all in the name of justice.

For an excellent study on this troubling trend, see this expertly reasoned book by Loretta J Ross:

I may not agree with all of her beliefs, but I sure do resonate with her heart and know that I have loads to learn from her approach. For an introduction to this author and her message, see this interview:

The good news is, this is a time in history when the Church can really offer our world something different than society's current ethical flavours and fashions. This is a time for righteousness to lead the way. And I'm excited to be part of that city on a hill.

So where does all this leave "justice" in the life of the church? I am coming to the conclusion, along with Jesus and the New Testament writers, that it doesn't. Righteousness is our calling: high moral standards plus mountains of mercy in the midst of failure to meet those standards. While our world pursues social justice, may the church offer the alternative of social righteousness.

The Church is called to be a society that offers everyone around us a contrast to the world's ways of top-down power and punitive justice. When matters of sin or injustice arise, this is our opportunity to demonstrate that contrast. This is our chance to proclaim the Gospel with our lives together. Church gatherings should feel more like AA meetings than protest rallies.

I will leave it to the world to fight for justice. I want to work for love.

You See It Too, Don't You

When a church, a denomination, or any Christian organization becomes fixated on justice instead of righteousness, well then, in the words of Shakespeare's Hamlet, “Something is rotten in the State of Denmark.”

Many Christians might sense that something isn't right, but they find it hard to formulate the words, especially in our increasingly hostile environment. It can be especially stifling when we feel like everyone, the majority, the masses, the mob is on the justice train, eager to write off sinners while advocating for the oppressed. Those of us who are more observant and perhaps sensitive to our surroundings may end up questioning if we are missing something that everyone else is tuned into.

If this describes you, here are two things to remember:

At various times in the history of the Western Church, the majority of Christian leaders supported everything from slavery, to wars, to witch burnings, to the torture and execution of heretics. In the words of my friend Brian Zahnd: "The majority is almost always wrong." (Jesus taught this same truth in Matthew 7:13-14.) Let's not mistake "widespread" for well-founded.

In the case of justice advocacy, the "majority" may not be as "major" as they appear to be. Here's why I say this...

By nature, justice oriented Christians are often more outspoken, while grace and mercy oriented Christians tend to be more gentle, patient, peaceable, and other fruit of the Spirit. So, while justice oriented Christians get louder, mercy oriented Christians get more quiet, trying to figure out what the hell is going on (a phrase I use intentionally). This dynamic gives the impression that justice is what Christianity is all about. The crowd of Christians all seem to be in agreement, while individual Christians are left wondering: "Am I the only one who senses that something isn't right?"

I know this is true because hundreds of you have spoken quietly to me about this very phenomenon, and because I've watched it happen, bewildered and beleaguered, all from a front-row seat. So this is my opportunity to validate what you are seeing, sensing, and are suspicious about - yes, something is off, something is weird, something is wrong in the Church today. And it feels like everyone is just marching along over the same cliff of justice mongering while biblical righteousness if forced to take a back seat.

So here is my chance to assure you, you're not alone, there is more of us than we might imagine. What you're seeing is real... while undiscerning people are joining the pile-on parade, many of us are afraid to admit out loud: The Emperor really does have no clothes.

I don't know what to do about this, beyond quietly supporting one another. I surely would not want to encourage the more humble compassion-oriented Christians to become as loudmouthed and belligerent as some of the more outspoken justice-oriented Christians who lead the parade these days. All I can think to do for now is provide this simple encouragement as well as an opportunity for us to find one another amidst the madness. If you'd like to connect with one of our small church groups in person or online, check out our small church page here.

With this I close: Is there a better word?

If you've made it this far, chances are you're not just a Christian, but a nerdy Christian. For people like us, the word "righteousness" feels familiar. But this may not be the case beyond our small circles.

While talking about this topic with my daughter, she pointed out something to me that I need to take seriously: "righteousness" feels like a distinctly religious word, like we are trying too hard to be pious and persnickety. It feels stuffy and inaccessible to the average English speaker outside the Church. So the word rarely gets used unless used negatively, as in calling someone "self-righteous".

Maya makes a solid point. A word is only useful if it gets used, embraced, and understood, and there are some real hurdles to this happening with the English word "righteousness".

This is one advantage of the word "justice" - it is common and feels accessible. So what should we do? Are there other more accessible words that can do the work of expressing all that "righteousness" means?

As I draw this article to a much overdue closing, I'm asking for your help. Do you have any ideas of what we should label, in popular conversation with our non-church friends, this thing that Jesus champions? I'll go first. Here are some options:

Use "justice", but always with a qualifier: "restorative justice" or "reparative justice". The advantage is that these words are known and accessible. This phraseology meets people where they are at. The disadvantage is that it still seems to champion "justice" in some form, which could unwittingly lead to more misunderstanding.

Use "righteousness" but always, or often at least, take the time to explain it as right-relatedness. This is more accurate, but also more cumbersome.

Switch the order of emphasis: just say "right-relatedness" as your primary way of describing this value, and sometimes explain that this is captured in a Bible word called "righteousness".

Use "rightness" or "in-the-rightness" or "up-rightness". This could be helpful, but ironically could also sound a bit self-righteous.

Something else all together?

So, now it's your turn. Comments are open. I would love to hear your suggestions, feedback, questions, or other thoughts you have about this article. Thank you!

Comments